The Delta Variant

The Delta[1] variant has substantially increased COVID risk, including for vaccinated people. We have adjusted the microCOVID calculator to provide updated numbers. Vaccines still provide substantial protection, but it’s gotten more complicated — read on to learn more about the latest findings, and please consider visiting the calculator to get updated risk numbers for your activities and relationships.

What does the Delta variant mean for me?

The Delta variant’s increased infectiousness means that COVID cases are surging faster than they used to. We now encourage you to check microCOVID at least weekly or use the risk tracker. You may want to make very different choices from one week to the next about activities like grocery shopping without a mask, dining, attending indoor parties, or going to bars/clubs. We saw the chance of infection from Indoor dining, fully vaccinated with Pfizer increase 7x within one week in Santa Clara County, California![2]

One thing that the Delta variant hasn’t changed is the effectiveness of simple precautions. In particular, shifting activities from indoors to outdoors still reduces your risk 20x as long as you maintain a distance of at least 3 feet (1 meter). N95 and KN95 masks are still extremely effective when used properly and are now available cheaply online.

Still, the Delta variant has affected the consequences of contracting COVID. We’ll discuss the risk of hospitalization, death, long-term symptoms, and of passing the infection to the people around you.

Avoiding hospitalization/death

The microCOVID risk budget[3] is based on the risk of infection. Infection risks have gone up for both vaccinated and unvaccinated people, though the risk is still much lower if you’re vaccinated. Thankfully, people who are fully vaccinated still have a low chance of being hospitalized or dying. [4]

Some folks have asked us if this means they should tolerate a higher risk budget, since the badness of developing COVID is lower. We think this has some merit, but please see the sections below for strong reasons why developing COVID can still have high costs for you and the people around you.

Avoiding long-term COVID symptoms

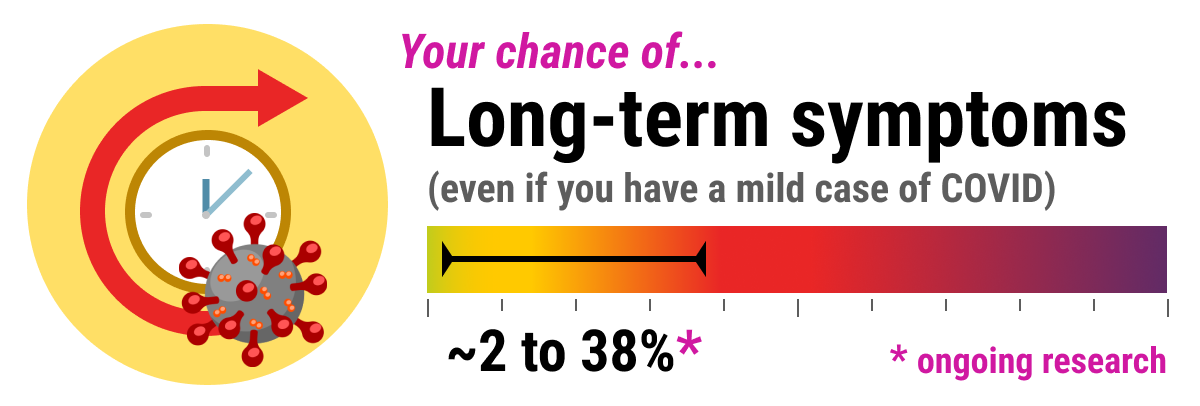

Long COVID (or PCS, Post-COVID Syndrome) refers to symptoms that linger months after initial infection, primarily including fatigue and respiratory problems, along with a wide range of other symptoms including pain and cognitive impairment.

There’s a great deal of uncertainty about how to monitor or diagnose long COVID right now. The lowest estimates are around 2%, which is already alarming given that it indicates potential long-term impairments for millions of people worldwide. Other studies show that it may be far more common than that, perhaps as high as 38%![5]

We do know that you can develop long COVID even if you’re vaccinated and even if your acute symptoms were only mild. Based on very rough evidence from previous variants, we estimate that vaccination does reduce risk, but only by about half. (See a deep-dive analysis by contributor Matt Bell for reasoning behind the vaccine estimate).

For less-vulnerable, vaccinated people, long COVID is likely a larger source of potential harm than hospitalization or death from acute COVID symptoms. At this time it’s very hard to quantify that harm, especially for Delta variant cases, and it will likely be several months before we have the data to do so.

With the incomplete information available today, some microCOVID contributors are accepting 2x the infection risk they did prior to being vaccinated, but we are not yet comfortable making this a general recommendation. We expect to have better guidelines in the future as scientific knowledge progresses and we know more about long COVID, communicability, and possible new variants.

Protecting friends/family/children/strangers

The Delta variant disproportionately infects unvaccinated people. Some of these people are children under 12, for whom no vaccine has been authorized yet. Others cannot get vaccinated due to medical factors (like severe allergies, cancer treatment or immune system issues).

If getting vaccinated isn’t an option for them, then the next best way to avoid infecting someone is to avoid getting infected yourself.

You can also encourage the people around you to take simple steps to reduce their own risk. You can:

- help them move gatherings outdoors,

- encourage them to get fully vaccinated, and

- remind them to wear masks indoors (N95, KN95 and surgical masks will protect better than cloth masks, but any mask is better than none).

Conclusion

We hope this post resolves some of the uncertainty around Delta, or at least gives you sharper boundaries around what is and isn’t currently known. As always, the goal of microCOVID is to empower people to navigate the pandemic without giving up everything nor taking on more risk than they intended to.

For those who are interested, the next section will dig into the research studies and decision processes behind the latest updates to the microCOVID model.

Nitty Gritty: Changes to the microCOVID Model

Increased Transmissibility

The hourly multiplier for COVID transmission has increased from 9% to 14%. The transmission rate for housemates has increased from 30% to 40%. The transmission rate for partners has increased from 48% to 60%. These increases reflect recent studies demonstrating the R0 for the Delta variant is substantially higher than for the Alpha[6] variant.

Reduced Vaccine Effectiveness Against Infection

Data has shown that vaccines are less effective at preventing symptomatic infection by the Delta variant than they were for the previously predominant Alpha variant. Pfizer/Moderna/Sputnik V have been reduced from a 90% reduction to a 84% reduction. AstraZeneca has been reduced from 60% to 54%. Single doses for all of the above have been reduced from 44% effective to 24%.

Johnson&Johnson’s single dose vaccine effectiveness reduced from 72% to 64% effective. Johnson and Johnson’s phase 3 study included separate data for subtrials run in North America and in South Africa. ~95% of cases in North America were of the original strain, and ~95% of cases in South Africa were of the Beta[7] variant. Antibody studies have demonstrated that the Beta variant has achieved equal or greater antibody escape compared the Delta variant. We thus use the J&J vaccine’s efficacy against the Beta variant as a stand-in approximation for its efficacy against the Delta variant while we await publication of J&J clinical trial data for the Delta variant.

Combining the effects of increased transmissibility and reduced vaccine effectiveness against infection, our model says that if you are fully vaccinated with Pfizer/Moderna/Sputnik V, then 60 minutes of exposure to someone infected with the Beta variant is equivalent to 25 minutes of exposure to someone infected with the Delta variant.

I heard that Pfizer’s vaccine is only 64% effective in Israel. Why is microCOVID treating it as 84% effective?

We dug into claims that the effectiveness of vaccines in Israel is 64% but had concerns about the methodology. These reports control for “age group (16–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years), sex, and calendar week” (Haas et al) but not individual behavior. Since Israel’s policy allows vaccinated individuals to participate in many activities with high risk of exposure (restaurants, movie theaters, etc. without masks), we hypothesize that the 64% effective number captures a combination of reduced efficacy of the vaccine vs the Delta variant AND increased opportunity for exposures.

Therefore, we instead used data from research in the UK that compared # of cases of Delta vs Alpha among vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals, which attempts to assess the vaccines’ efficacy in isolation (Bernal et al.), (Stowe et al.). These studies found 88% vaccine efficacy vs symptomatic COVID, which we adjusted to 84% to account for asymptomatic cases.

Delta is now believed to the the most common variant worldwide. Note that the WHO has started labelling variants with Greek letter names that are easier to remember than letter-number sequences and less stigmatizing than location-based names. In scientific circles, Delta goes by the name B.1.617.2. ↩︎

At our recommended caution budget, the 7x increase meant indoor dining went from a once-a-week activity to a less than once a month activity. ↩︎

The microCOVID calculator lets you estimate the risk of infection from social gatherings, errands, roommates, and other interactions. We compare it to your risk budget, which is the total chance of getting infected you’re willing to tolerate over a week or a year. ↩︎

Alpha is the new name for the B.1.1.7 variant, also sometimes referred to in the media as the “UK variant.” ↩︎

Beta is the new name for the B.1.351 variant, also sometimes referred to in the media as the “South Africa variant.” ↩︎